Brains or Beauty?

Online Dating Market代写 We study partner preferences for education and attractiveness by conducting a field experiment in a large onlin

Causal Evidence on the Returns to Education and Attractiveness in the Online Dating Market*

Johan Egebark Mathias Ekström Erik Plug

Mirjam van Praag

Abstract Online Dating Market代写

We study partner preferences for education and attractiveness by conducting a field experiment ina large online dating market. Fictitious profiles with manipulated levels of education and photoattractiveness send random invitations for a serious relationship to real online daters. We find thatmen and women prefer attractive over unattractive profiles, regardless of own attractiveness. We also find that high-educated men prefer low-educated over high-educated profiles as much as high- educated women prefer high-educated over low-educated profiles. With preferences similar forattractiveness but opposite for education, two groups are more likely to stay single: unattractive, low-educated men and unattractive, high-educated women.

*Affiliations: Egebark: Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN); Ekström: NHHNorwegian School of Economics, and IFN; Plug: Amsterdam School of Economics, TinbergenInstitute, IZA, and UCLS; van Praag: Copenhagen Business School, Amsterdam Business School,Tinbergen Institute, IZA and CEPR. We thank Ingvild Almås and Adriaan Soetevent, and seminarand conference participants in Copenhagen, Glasgow, Lofoten, Milan, and Nuremberg for their comments and suggestions. We also thank Tim van der Weert for his outstanding research assistance. The project was approved by the ethical review board at the Amsterdam School of Economics.

1. Introduction Online Dating Market代写

How do partner preferences shape partner matches? While this question has long interested socialscientists from all disciplines, their answers need not be the same. If individuals prefer partnerswith traits similar to their own (or prefer traits in partners in similar ways), partner preferences can explain positive assortative matches, which are widespread in marriage markets. 1 If,instead,individuals hold preferences for a traditional family (with traditional roles of family specialization),partner preferences can explain why traditional matches are so persistently observed in marriage markets.2

It has proven difficult, however, to find credible answers and carefully identify the impact of partner preferences on partner matches using realized partner matches alone. One difficulty arises because of search frictions. Individuals generally self-select into clubs, schools, jobs, and neighborhoods. If search frictions make individuals more likely to meet their partner in self- selected environments (Kalmijn, 1998), they are also more likely to end up having a partner withtraits similar to their own, regardless of partner preferences. Another difficulty arises because ofpsychological and social frictions. Partner choices are based on a combination of rationality andemotions (Finkel et al., 2012).

Individuals may,

for instance, fear rejection or follow the socialnorm about what is considered an attainable partner. If fear of rejection or norm conformity makesindividuals act strategically and shy away from partners they consider attractive but unattainable,realized partner matches do not reflect partner preferences, even in the absence of search frictions. Online Dating Market代写A final difficulty arises because of correlated traits. Any observable trait similarity between partnerscould be due to similarities in other related traits that are observable to potential partners but not to researchers. Whenever observable and unobservable traits are correlated, either between or within partners, the estimated partner preferences for specific traits will be biased.

Notwithstanding these difficulties,

it is important to isolate partner preferences from frictions. It is of interest to us, economists, to better understand the degree of inequality among families; if, for instance, individuals prefer partners with traits similar to their own, partner preferences would lead to greater inequality in family income. But it is, of course, of much morethan economic interest to those singles and divorcees searching for a partner. Few choices in life are as important as partner choice; if partner choice reflects frictions, not preferences, there is scope for serious welfare gains.

1Partners generally match on intelligence,

education, social background, ethnic origin, religion, height, weight, attractiveness, and no doubt other traits too (Gale and Shapley, 1962; Becker, 1981). Economists call these patterns positive assortative matching. Sociologists call these patterns homogamy. Recent overviews on suchpatterns can be found in, for instance, Weiss (1997), Kalmijn (1998), Schwartz and Mare (2005), Fernandez,Guner and Knowles (2005), Belot and Francesconi (2013), and Browning, Chiaporri, and Weiss (2014).Online Dating Market代写

2 Recent examples of traditional match persistency are Bertrand et al. (2015) who find that relatively few wives earn more than their husbands; Bursztyn et al. (2017) who find that single women hide their professional ambition for potential partners; and Folke and Rickne (2016) who find that divorce risks rise when women get suddenly promoted.

In this paper,

we identify partner preferences by conducting a correspondence test experiment among online daters on one of the largest online dating sites in the Netherlands. Wepost fictitious profiles with traits that are manipulated along two dimensions: attractiveness andeducation.

We focus on attractiveness (as measured by facial attractiveness) and education becausethese two traits are stable, mostly realized when online daters enter the online dating market, often considered substitutes in partner choice, a proxy for income potential (especially education),generally highly correlated between partners, and more highly correlated than most other traits.From these fictitious profiles, we then randomly sent out dating offers to a relevant set of onlinedaters and collected their responses. These responses measure partner preferences without biases, reflecting the true preferences for partner attractiveness and education. In total, we posted 12fictitious profiles and invited some 2,700 online daters for a date in the spring and fall of 2016.

We preview three of our main findings.

First, we find that response rates significantly risewith profile attractiveness. The positive impact of attractiveness on the likelihood to respond isquantitatively large, identical for men and women, and insensitive to the attractiveness of onlinedaters themselves. Second, we find, much to our own surprise, that men are more likely to respond to lower educated profiles, but not women. The gender difference in response rates to profile education is quantitatively large, and much more pronounced for more educated online daters;according to our estimates, university educated men show a clear preference for lower educatedwomen, while university educated women reject men with lower education than themselves. Third,we find no evidence that attractiveness and education are substitutable, and thus tradable, traits in response rates. The interacted impact of attractiveness and education is generally small and statistically insignificant.

To put these main findings into context,

the partner preferences we estimate predict positive assortative matching on attractiveness (so that the most attractive man matches with themost attractive woman, and so on) and negative assortative matching on education (so that themost educated man matches with the least educated woman, and so on). These sorting patternsimply the persistency of traditional matches: men and women mutually prefer to live in a traditionalrelationship where husbands have a stronger earnings potential than their wives. These sortingpatterns also imply that not everyone will find a partner: the two groups at risk are unattractive, low-educated men and unattractive, higheducated women. These implications are consistent with a wide range of recent empirical results.Online Dating Market代写

So far,

the economics literature linking partner preferences to partner matches has mostlyestimated structural marriage models using data on realized partner matches (see, for instance,Wong, 2003; Bisin, Topa, and Verdier, 2004; Choo and Siow, 2006; Gautier, Svarer, and Teulings, 2010). It is only recently that economists have begun to explore alternative strategies and data sources to extract partner preferences and their impact on partner matches, including revealed partner choice data from speed dating events and online dating sites.3

Our study relates to recent work that estimates partner preferences based on speed date events. Kurzban and Weeden (2005) draw their sample from one of the largest speed dating companies in the US and find that male and female speed daters are much more likely to proposeto attractive speed date partners. They do not find much for more educated speed date partners,though. Fisman et al. (2006) organize speed date events among Columbia university students and find that all speed daters like to date attractive and intelligent speed date partners, where men prefer attractiveness over intelligence and women prefer intelligence over attractiveness.

Belot and Francesconi (2013)

rely on speed date events in the UK and find that male and female daters valueattractive speed date partners (as measured by their physical traits). Their results further indicate that male speed daters like to date more educated partners who work in less prestigious occupations, whereas female speed daters like to date partners who work in more prestigious occupations, regardless of their educational attainment. Since these traits (physical attractiveness,education, and occupational status) are correlated with each other, it is not a priori clear whichpartner traits shape partner preferences. Also, it may be unrealistic to assume that speed dating does not suffer from psychological and social frictions.4Online Dating Market代写

Closest to our study is work by Hitsch,

Hortaçsu, and Ariely (2010) and Skopek, Schulz and Blossfeld (2011) who rely on online dating information to estimate partner preferences.Hitsch, Hortaçsu, and Ariely sample online daters in two major US cities and find that, regardless of gender, all online daters are more likely to send a first-contact email to more attractive profiles.Only female online daters are more likely to initiate contact with more educated profiles. For male online daters, the likelihood to first contact a more educated profile is slightly negative and statistically insignificant. Skopek, Schulz, and Blossfeld use online information in Germany andfind that male and female online daters shy away from profiles that are less attractive than themselves, but only male online daters dare to initiate contact with profiles that are physically more attractive than themselves.

In case of profile education,

both males and females seem to avoid contact with profiles who have lower education than themselves. Skopek, Schulz, and Blossfeld also find comparable online response patterns when they analyze reply behavior to selective contact emails (which is the outcome in our study). Insofar as online daters initiate contactstrategically, these studies obtain biased measures of partner preferences. While Hitsch, Hortaçsu,and Ariely find little support for strategic behavior, Skopek, Schulz, and Blossfeld conclude that social frictions observed in assortative partner matches continue to affect online dating choices.The recent findings of Bapna et al. (2016) using online dating data from the US confirm the latterview; in fact, they provide experimental evidence that online daters actually benefit from acting strategically.5

3A larger empirical literature elicits stated partner preferences from survey questions and vignette designs (Buss,

1994; Regan 1998; Stewart, Stinnet, and Rosenfeld, 2000; Almås et al., 2017). These studies generally find that men value attractiveness more than women, whereas women value education/earnings potential more than men do.Online Dating Market代写

4Finkel, Eastwick, and Matthews (2007) list three other limitations common to speed date studies. First, samples of participants of speed date events are quite selective, which limits the external validity of speed date results. Second, the main outcome is mostly a realized speed date relationship, which is not necessarily informative about a longstanding serious relationship. And third, participants in speed date events may feel embarrassed about participating, and as a result date differently than they would otherwise date.

What does our study add to this recent work

on partner preferences? Well, we are the firstto apply the correspondence test experiment in an online dating setting. As such, we solve several difficulties that are common to studies on the impact of partner preferences on partner choice. First, we account for search frictions; that is, we believe that search frictions in online dating markets are as good as absent (as in the speed date studies but not in the search and matching studies).Online Dating Market代写

Second, we account for psychological and social frictions; that is, we expect that incentives to act strategically quickly fade out once online daters are invited for a date by profilesthey consider attractive but unattainable. And third, we account for correlated (profile) traits; thatis, we introduce fictitious profiles with manipulated traits that are uncorrelated with each other, so that any response differences can exclusively be attributed to differences in attractiveness and education, and not to something else.

As with all the other empirical strategies,

the correspondence test methodology has itslimitations. One limitation is that our main outcome is responding to a dating offer rather than theactual partner match. While the response captures how men and women value attractiveness andeducation in an online dating offer, we also know that this response is the first necessary step foronline daters to seriously match. Another limitation is that our focus is on online dating behavior, which may reflect preferences for casual and short relationships rather than serious and longstanding relationships. To alleviate this concern, we posted fictitious profiles of online daters Online Dating Market代写

5The normative dating rule in the context of online dating is that male online daters initiate the first contact oncefemale online daters have signaled their interest (through an online record of their profile visit). In an experimentwhere a randomized group of online daters could visit other profiles unrecordedly, Bapna et al. (2016) find that particularly female online daters are less likely to find a date/partner because of their inability to leave a signal.Note that Bapna et al. do not exploit trait information of the online daters.

who were all in their 30s,

looked for a serious relationship, and wanted to have children. We furtherconducted our analysis on a sample of online daters with the same profile characteristics. While itis possible that some of the online daters provide misleading profiles and falsely report to look fora longstanding relationship with children, we also know that online dating is one of the primary search channels for a serious relationship; according to Rosenfeld and Thomas (2012), online dating is nowadays the main search channel for partners and particularly helpful for singles and divorcees in thin marriage markets.

The remainder of our study proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides details about the experiment. Section 3 outlines the results. Section 4 interprets the results. Section 5 concludes.

2. The Experiment Online Dating Market代写

We employ a correspondence test to identify partner preferences. This is the common method todetect discriminatory preferences in the context of the labor market (Bertrand and Mullainathan, 2004), the housing market (Ahmed and Hammarstedt, 2008) and the second-hand market for customer products (Doleac and Stein, 2013). In the context of the online dating market, the method involves letting fictitious profiles with different (combinations of) traits randomly contactpotential dating partners.6

In particular,

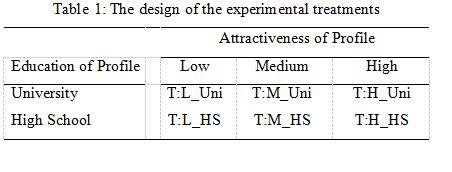

we exogenously vary two profile traits that are often listedas key traits in partner search: education and (photo) attractiveness (e.g. Kurzban and Weeda, 2005;Todd et al., 2007; Belot and Francesconi, 2013). Table 1 shows the six treatments we employ in the experiment, representing different combinations of three attractiveness levels and two educational levels. We run this design for men and women separately, thereby allowing for genderspecific measures of returns to education and attractiveness, and potential interactions thereof (e.g., Fisman et al., 2006). In total, we post 12 fictitious profiles on a dating website, one for each treatment and gender. Below, we describe the particular website that we use, the construction of profiles, the photo selection procedure, and the experimental setup.

6An alternative correspondence test setup would be to send multiple invitations to one online dater. We consider this problematic because of detection risk.

Context Online Dating Market代写

Our experiment takes place among users of one of the larger online dating websites in the Netherlands. Online dating has become the main search channel for partners and is still growing.To illustrate this, a Pew Research Center survey found that 60 percent of Americans think online dating is a good way to find a partner; nearly half of the population knows people having (successfully) used online dating to find their partner (Smith and Anderson, 2016); 20 percent of current committed relationships began online, and seven percent of marriages in 2015 were between couples that met on a dating website (Thottam, 2016). In the Netherlands, more than 13 percent of couples that started living together in the period 2008-2013 met online (Kooiman and Latten, 2014).

The dating site that we use has various appealing features for our purposes.

First, it is large, easily allowing for an experiment of the size that we wanted to conduct. Second, members are observably representative of the Dutch population in the age and education groups that we study(see below). Third, the entry fee for the first three months is around 45 euro, making it relativelyless attractive to less serious individuals compared to free dating sites. Fourth, the website doesnot require users to fill out and provide results from psychological tests and does not use smart matching techniques, which would compromise our design.Online Dating Market代写

Upon joining the website,

users create their personal profile, often including one or morephotos, after having provided their email address and a debit/credit card number for payment of the subscription fee. A profile consists of a username and formatted information (chosen from listed options) about age, gender, level of education, place of residence, religion, height, weight,occupation and life style (sports, smoking, drinking). Users further list the main reason for joiningthe service, (i.e., friendship, date, serious relationship), provide their photo(s) and write a (freeformat) short introduction about themselves. The dating website posts these profiles and photos after a quick screening on irregularities.

Profile design Online Dating Market代写

Our aim is to construct twelve fictitious profiles that appear as similar as the real ones. Our fictitious profiles are born in 1985, live in Amsterdam, are heterosexual, not religious, of averageweight and height, live an active life (no smoking, no drinking, regular exercise), and aim at a long- term relationship with children. Our fictitious profiles do not provide occupation and income information. There are two points to note about these profiles. First, profiles with an explicit demand for a long-term relationship and children in combination with the birth year (people in their early 30s) signal the desire for a serious relationship. Second, profiles without occupation and

income information are realistic profiles:

that is, the online profiles under study do not offer income options, and most profiles leave the occupation option open. Also, profiles without occupation and income information allow us to interpret the effect of education more broadly as the effect of education and everything else that education affects, including occupation and income status. Almås et al. (2017) refer to education as one potential measure of someone’s earnings potential and we use the same terminology here.7Online Dating Market代写

We use six profiles for each gender (see Table 1). The six profiles have different usernames,education levels and photos. We assign different usernames based on popularity ratings of Dutch names for the 1985 cohort.8 The profiles only hold highly ranked usernames to overcome the concern that online daters may respond differently to first names that appear odd and/or reflectsocial background (Freyer and Levitt, 2004). We assign two levels of education. The high-educated profiles hold a five-year university degree, whereas the low-educated profiles hold a high-school degree.

We use these two categories to create a significant distance in terms of education,

while at the same time making sure that the groups are not too marginal (e.g., high school drop outs or people with doctor degrees). About 11 percent of the Dutch population between 15-64 years oldhas an equivalent university degree and about 41 percent has only completed high school (Statistics Netherlands, 2014).9 We finally assign six profile photos (for each gender) representing three different attractiveness levels. For each education category we use one profile photo capturing low attractiveness, one photo capturing medium attractiveness, and one photo capturing high attractiveness. Below, we provide details about how we obtain the photos and how we rate them.

Profile photos Online Dating Market代写

We needed two equally attractive photos per gender and attractiveness level (one for each education level).10 We selected these photo pairs (6 in total) as follows.

We first collected photos of 88 males and 54 females (all white and around 30). These potential profile photos were taken from personal networks, complemented with photos taken from the website dreamstime.com, which is a website where anyone can upload photos for

7Education may also serve as a signal for other traits not explicitly stated in the profile (e.g., IQ and social background).

8The male names are: Martijn, Stefan, Jeroen, Erik, Sander and Dennis. The female names are: Marieke, Maria, Joyce, Esther, Sanne, and Danielle.

9The remaining fraction mainly consists of people with a three-year bachelor degree. The Dutch acronyms representing the two education levels that we use in our study are WO (university) and MBO (high school).Online Dating Market代写

10We need two profile photos per attractiveness level because of the practical impossibility to assign the samepicture to two different profiles (with high and low education). The website would probably have stopped anyattempt to use the same photo for different profiles at the same time and it would otherwise have drawn attention from other website users. We deemed it important to post the profiles simultaneously so that we would alwayscompete in the same market (i.e., avoiding confounding time effects).

commercial (or other) use. Our aim was to gather photos spanning a wide range of attractiveness (according to our own insights).

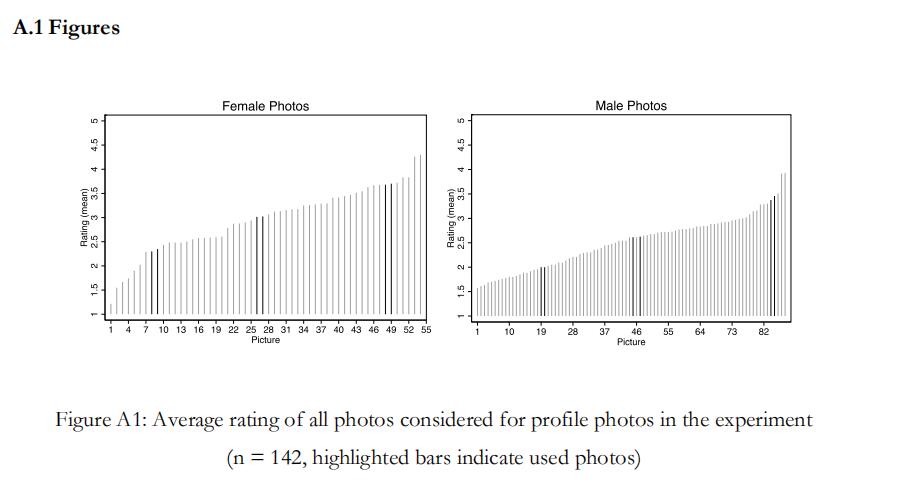

We then went to the online labor market Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) to obtainobjective measures of attractiveness for each photo. For 1$ in return, we asked 204 male membersto rate equal sets of female photos, and 96 female members to rate equal sets of male photos, using a 1-5 scale where 5 corresponds to very attractive and 1 to very unattractive. We use the averagephoto ratings as our measure of attractiveness. The ratings show much variation in attractiveness across photos (see Appendix Figure A1).Online Dating Market代写

We next picked various photo pairs with very similar ratings, from the high, the mediumand the low segments of the attractiveness distribution. We returned to MTurk for pairwise photocomparisons, asking 850 male and 531 female members to pick the most attractive person of eachpair. The order of appearance as well as the photo position (left or right) was random. Based onthe pairwise comparisons, we ended up with three equally attractive photo pairs per gender, onefor each attractiveness level (see Appendix Table A2).11 Furthermore, we switched the educationlevel of the photo across the two rounds of data collection (in the spring and fall) to ensure that the photos do not confound the effect of education.12

Sample

The subject sample consists of active members of the website in two periods: May-June 2016 and October-November 2016. The members in the second sample were sufficiently new to avoid overlap. We select our sample of potential partners based on some exogenous trait similarity between our profiles and website members; that is, we restricted the sample to website memberswho had filled out all relevant information and posted a photo, were heterosexual, were between 25 and 35 years old, and lived in the provinces Zuid-Holland, Noord-Holland or Utrecht, i.e. not too far from the inviting profiles in Amsterdam. To further ensure that we measure partner preferences in serious relationships, we restricted the sample to website members who were looking for a long-term relationship, and who wanted to have children.Online Dating Market代写

Next, we hired a professional data scraper, who built a robot that browsed the website,identified the relevant sample, and downloaded each subject’s profile photo, education level, area of residence, age and gender. The photos and education information are crucial for analyzing

11One of the intended pair of profile photos was rejected by the dating website.

We managed to submit another pair of profile photos of equal attractiveness. However, we did not expose that pair of photos to the pairwise test.

12Thus, we can measure returns to education in two ways: within a round across profile photos (of the sameattractiveness level), or within profile photos across rounds (see section 4).Online Dating Market代写

matching preferences in the attractiveness and the education dimensions. The scraping produceda sample of 2,672 (1,554 male and 1,118 female) online daters who are eligible for receiving an invitation message from one of our 12 fictitious profiles.

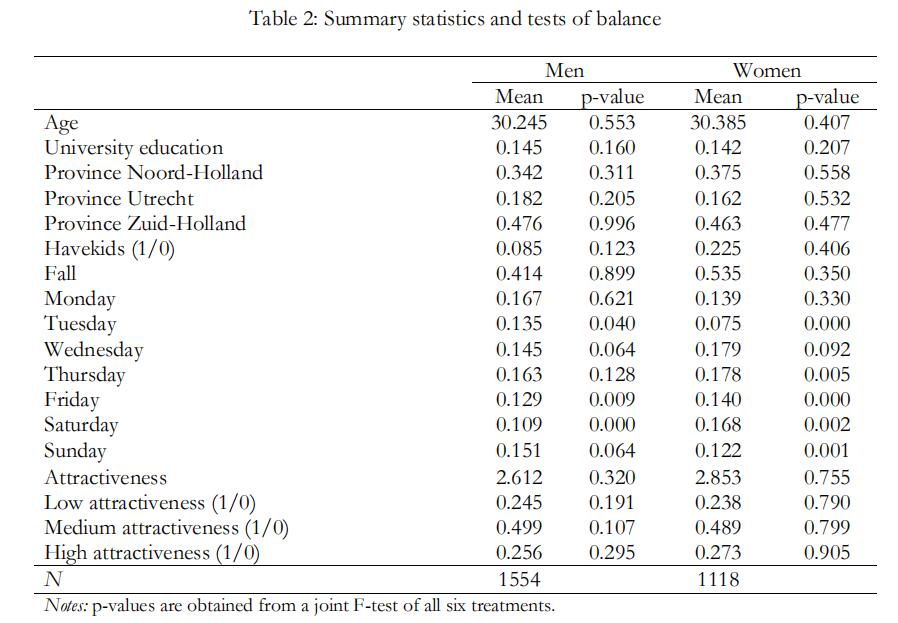

Table 2 presents sample averages per gender.

We highlight a few of the background variables. In conformity with the design, the average (male and female) subject is thirty years old(between 25 and 35). Moreover, the subjects live in the three provinces close to Amsterdam, inproportion to the actual population distribution (47, 36 and 17 percent). The share of memberswith a university degree is slightly higher than in the Dutch population between 15 and 65 yearsold (14 versus 11 percent), which is not surprising since we focus on younger cohorts. As in thegeneral population, however, the share with a university degree is similar across gender (Statistics Netherlands, 2017).

We returned again to MTurk

to obtain an attractiveness measure of each subject’s downloaded profile photo, using the same 5-points scale as before. We use as the level of attractiveness the average of ten photo ratings (by the opposite gender) taken from 514 MTurkpanel members. We construct low, medium and high attractiveness categories, using the 25th and 75th percentile as cut-offs.13Online Dating Market代写

Table 2 also reports p-values from joint orthogonality tests across the different profile treatments. Their insignificance shows that the random assignment of online daters to the six treatments per gender worked well. There is one exception. We see that the day of the week when the contact was made varies across treatments. This is unproblematic and follows from the staggered implementation process, which we describe in more detail below. In our empirical analysis we account for the day of the week a message was sent.

Sending Messages

The online dating members in our sample were randomly assigned to one of the six profiles of each gender from whom they receive a message. The profiles sent out identical messages, expressing their interest in the subject and clearly stating that they are looking for a long-term relationship. The message also includes an invitation to meet in real life. The invitation message isfound in Appendix A3. Each profile sent out roughly 120 messages in each round. Hence, we sentout 2,672 messages in total. For technical and practical purposes (i.e., passing the initial dating site

13Our fictitious profile pictures neatly fall in the same categories.

screening), we restrict the number of messages sent from each profile to 20 per day, using variouscomputers and locations for different profiles. We further post each profile with a one-day lag.Table 3 illustrates the gradual implementation of posting profiles and sending out messages.Online Dating Market代写

Table 4 summarizes the data on response behavior that we collected within the first fourweeks after the initial invitation message. About half of the invitations were opened. The response is recorded as being positive as long as it is not a definite rejection. The shares responding andresponding positively are almost similar, showing that online daters basically only respond whenthey are interested. We use a positive response as the main outcome variable throughout.14 In linewith earlier research (e.g., Hitsch, Hortaçsu, and Ariely, 2010), we find lower response rates for women (13 percent) than for men (29 percent). Women are also slower when responding: the median (average) is zero (seven) days for men and one (nine) day(s) for women. Online daters whorespond positively receive a polite rejection message from the profile indicating that they are no longer interested. The rejection message is found in Appendix A3.

3. Results Online Dating Market代写

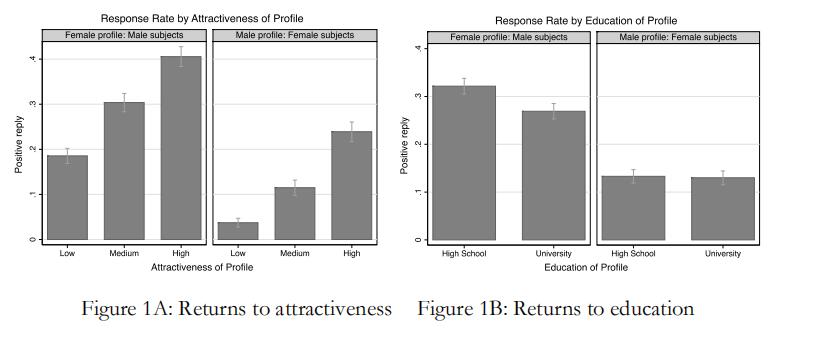

In this section we present causal evidence on the returns to attractiveness and education in online dating, using both figures and tables. The results are divided by gender. The figures visualize the average response rates to invitations from low-attractive, medium-attractive, and high-attractive profiles, as well as from low-educated and high-educated profiles. The tables report estimates from simple linear probability models regressing the response on profile attractiveness and education, accounting for both profile and subject characteristics.

Main results

14We are not conditioning on subjects opening the message. Since people can see a thumbnail photo and also search the profile username on the website before replying, that would cause a potential bias in our estimations.Online Dating Market代写

Figure 1A demonstrates the importance of attractiveness in the dating market. We see that high- attractive profiles receive many more responses than intermediate-attractive profiles, and that intermediate-attractive profiles receive many more responses than low-attractive profiles. Women are much less likely to respond to profile invitations than men. For example, 20 percent of the men respond to the invitation from the lowattractive profiles whereas less than 4 percent of thewomen do so. However, the relationship between response rates and attractiveness appears to be equally steep for male and female online daters.

Turning to education,

Figure 1B shows interesting gender differences. Women (on average) do not care about the level of education of their potential partner: their response ratesare almost identical for the two male profiles. In contrast, men seem to care, and persistently prefer low-educated profiles over high-educated profiles.

Table 5 contains the estimates from our response regressions. In columns 1 and 2, theestimates echo what we already saw in figures 1A and 1B: response rates of both men and women significantly rise with profile attractiveness, and response rates significantly fall with profile education for men, but not for women.

For profile attractiveness,

we find that profiles with high-attractive photos are 20 percent points more likely to receive a response than profiles with low-attractive photos, regardless ofgender. These are large effects: a 20 percent point rise in response rates represents a 200 and 600percent rise in male and female responses, respectively. These latter differences arise because of the large gender differences in the baseline response rates. In column 3 we test for gender differences in response rates measured at the margin. While we find that male daters are somewhat more responsive to intermediate-attractive profiles than female daters, we believe that the high p- values for the high-attractive profiles indicate that attractiveness is more or less of equal importance to men and women.Online Dating Market代写

For profile education,

we find that female daters do not respond to profile education: the point estimate is close to 0 and statistically insignificant. In contrast, we find that men are 5.1 percent point less likely to respond when we increase the education level of the female profile from high-school to university, which is equivalent to 25 percent fewer responses.15

15We calculate that a one standard deviation increase in facial attractiveness raises the average response rate byabout ten percentage points, regardless of gender. We also calculate that with a one standard deviation increasein educational attainment (measured in years of schooling), male online daters are about two to three percentage

In the remaining columns, we also test for interactions between attractiveness and education. We find that none of the interactions is statistically significant, neither for male nor forfemale daters. Apparently, online male daters are not more forgiving towards female profiles withhigh levels of education when these females are more attractive. Education and attractiveness seemnot to be substitutable. Likewise, we find no evidence of complementarities between attractiveness and education either.

Heterogeneous responses based on own education and attractiveness

To examine whether the responses are heterogeneous across different education and attractiveness online dater groups, we estimate our response regressions for different subsamples. Table 6 contains these estimates; Panel A shows the results for female online daters, and Panel B for male online daters.Online Dating Market代写

The estimates for attractiveness indicate that all the online daters in the subsamples (withand without a university degree, being less or more attractive than average, being men or women)respond with a higher likelihood to more attractive profiles. Moreover, all online daters respondequally to profile changes in attractiveness: all the estimated differences across groups (reportedin columns 4 and 8) are small in size and statistically insignificant.

The estimates for education

for female daters show that those with a university degree arenot so indifferent to the education levels of the profiles (as is the average female). We find that female university graduates strongly prefer male university graduates. Clearly, these female daters do not want to down-date, holding everything else constant. The estimates for education for menalso show the strongest responses in the subset of males with a university degree. But this time wefind the opposite pattern: male university graduates strongly prefer females with a lower level of education, i.e., high-school degree.16

points less likely to respond than female online daters.

For the most educated online daters, the gender difference in response rates is much larger and amounts to ten percentage points (see also Table 6).Online Dating Market代写

16Instead of using pairs of profiles for each attractiveness level to identify the effect of education (while switching photos between profiles halfway through the experiment), we can use an alternative strategy to identify the returns to education. We can estimate a photo fixed effect model by exploiting the fact that the exact same photo was coupled with a different education level in the spring and fall. The results (available from the authors) confirm the robustness of our earlier results: Men prefer women with lower education regardless of their owneducation level. Women without a university degree are indifferent to a subject’s education level, but women with a university degree prefer profiles with a university degree.

4. Interpreting the results Online Dating Market代写

In this section we take one step back and discuss our results in terms of partner preferences and partner matches.

On partner preferences, the most prominent families of partner preferences used to predict realized partner matches are (i) homophilic preferences; (ii) universal preferences; and (iii)traditional preferences. Homophilic preferences imply that both men and women prefer partnerswith traits similar to themselves (Walster et al., 1966). Universal preferences imply that men and women prefer traits in partners in similar ways, independent of their own traits (Buss, 2006).

Traditional preferences

(or genderidentity preferences) imply that men and women respond to partner characteristics according to traditional gender norms and (anticipated) familyspecialization; that is, women prefer men who are better educated than themselves (because bettereducated partners can offer more resources for raising children) and men prefer women who are lesser educated than themselves (because lesser educated partners may make men feel moresuperior) (Eagly and Wood, 1999; Bertrand, Kamenica, and Pan, 2015; Folke and Rickne, 2016;and Almås et al., 2017). Our findings are most consistent with universal partner preferences for attractiveness and traditional preferences for education.17Online Dating Market代写

On partner matches,

we do not have information about realized partner matches. But we can speculate and use these partner preferences – in a deferred acceptance algorithm – to predict patterns of partner matching. If marriage markets operate as if the most preferred men and womenchoose their partner first and so on, our partner preferences imply that most men and women endup in traditional relationships where husbands are better educated than their wives, possibly withtraditional roles of household specialization.

These traditional matches are mutually preferred

by both partners and (perhaps therefore not surprisingly) consistent with the traditional partner matches persistently observed in marriage markets with more educated women than men (Bertrand, Kamenica and Pan, 2015; Folke and Rickne, 2016; and Almås et al., 2017). Note thatthe traditional matches we predict should not be seen as evidence against assortative matches, butas suggestive evidence in favor of frictions; that is, educated men and educated women are morelikely to marry each other because of frictions, not because of preferences. Frictions in marriage markets are real, and as long as people tend to meet partners at work, in school or within their

17While the response behavior of women is consistent with both traditional and homophilic preferences, our observation that men explicitly prefer low-educated women over high-educated women rules out homophilic preferences.

social network,

partners will more often than not resemble each other along many traits— independent of their underlying partner preferences.Online Dating Market代写

Our partner preferences further imply that not every man and woman will find a partner. The least preferred groups (unattractive, low-educated men, and unattractive, high-educated women) are the last in line to choose a partner. Since they indicate not to like each other, they maybe better off single. Again, we see that these partner preferences are remarkably consistent with real world behavior of unmatched men and women in modern marriage markets with more educated women than men. For unmatched men, there is evidence that the least educated men tryto find their partner elsewhere. Glowsky (2007), for example, shows that low-educated men in more developed countries increasingly marry women from less developed countries.

For unmatched women,

there is also evidence that high-educated women find it difficult to find a partner and get pregnant. Recent studies on singles in the US suggest that in marriage markets there are too few college-educated men to meet the partner demand of college-educated women (Klinenberg, 2012; Birger, 2015), and that female college-graduates shade their career ambitionsto possible partners (Burzstyn et al. 2017). Other recent studies on childlessness in women findthe highest share of childless women, as well as the highest IVF (in vitro fertilization) treatment rates among college-educated women (Bitler and Schmidt, 2012, Jalovaara et al., 2017; Lundborg et al., 2017). Although these studies do not consider childlessness under single women, we believe that childlessness is closely tied to being single.Online Dating Market代写

5. Conclusion

Few choices in life are as important and complex as partner choice. Partner choice involves, among other things, the partner preferences of oneself and others, which are difficult to observe. Our purpose here is to measure partner preferences and particularly examine how individuals valueattractiveness and education in a partner. We do this by running a large online dating experimentin which fictitious profiles with manipulated levels of attractiveness and education randomly invite real online daters for a date (exploring the possibility for a serious relationship with children). Using their responses, we are able to identify partner preferences without biases; that is, we obtaincausal returns to attractiveness and education by simply regressing response rates on our measures of attractiveness and education.Online Dating Market代写

Two key results about partner preferences emerge from our analysis.

Our first result is thatthe effect of attractiveness on the likelihood to respond is significantly positive, quantitatively large,identical for men and women, and insensitive to the attractiveness of online daters themselves.

Our second result is that the effect of education on the likelihood to respond is significantlynegative for men, but effectively zero for women. Most interestingly, when we explore how theseresponse rates vary with the education of online daters themselves, we find that high-educated men prefer low-educated profiles over high-educated profiles as much as high-educated women prefer high-educated profiles over loweducated profiles. Both results are consistent with men and women having universal (similar) preferences for attractiveness, but traditional (opposing) preferences for education.

Taken at face value, Online Dating Market代写

these traditional partner preferences can help us to better understandsome of the recent developments in marriage markets, including the persistence of (newly formed) traditional couples and the rise of single high-educated women and low-educated men. It is important to recognize, though, that we know little about how partner preferences develop overtime. In our experiment, we have measured partner preferences in a marriage market where youngwomen, year after year, continue to exceed men in terms of educational attainment in one of theworld’s most progressive countries.

18 With partner choice being so important, it is then natural toask why such a modern marriage market yields partner preferences that are so traditional. Perhaps partner preferences are stable and hardly change over time? Or perhaps it takes more time, spanning multiple generations, for traditional partner preferences to adapt? These are importantquestions that await future analysis, from economists and other social scientists.

References Online Dating Market代写

Ahmed, A. M., and Hammarstedt, M. (2008). Discrimination in the rental housing market: A field experiment on the Internet. Journal of Urban Economics, 64(2), 362-372.

Almås, I., Kotsadam, A., Møen, E., and Røed, K. (2017). Economic asymmetries in partnering: Empirical facts and theoretical foundations. Unpublished manuscript.

Apino, B., Esping-Andersen, G., and Pessin, L. (2015). How do changes in gender roles towards female employment influence fertility? A macro-level analysis. European Sociological Review, 31(3), 370–382.

Andersen, R., and Fetner, T. (2008). Economic inequality and intolerance: Attitudes toward homosexuality in 35 democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 52 (4), 942-958.

Bapna, R., Ramaprasad, J., Shmueli, G., and Umyarov, A. (2016). One-way mirrors in online dating: A randomized field experiment. Management Science, 62(11), 3100-3122.

Becker, G. (1981). A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Belot, M., and Francesconi, M. (2013). Dating Preferences and Meeting Opportunities in Mate Choice Decisions. Journal of Human Resources,48(2), 474-507.

Bertrand, M., and Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination. American Economic Review, 94(4), 991-1013.Online Dating Market代写

18 The Netherlands is one of the most progressive countries when it comes to (attitudes on) gender and marriage equality (Andersen and Fetner 2008, Apino et al. 2015).

Bertrand, M., Kamenica, E., and Pan, J. (2015). Gender identity and relative income within households. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(2), 571-614.

Birger, J. (2015). Date-onomics: How Dating Became a Lopsided Numbers Game. New York: Workman Publishing.

Bisin, A., Topa, G., and Verdier, T. (2004). Religious intermarriage and socialization in the United States. Journal of Political Economy, 112(3), 615-664.

Bitler, M. P., and Schmidt, L. (2012). Utilization of Infertility Treatments: The Effects of Insurance Mandates. Demography, 49(1), 125-149.

Browning, M., Chiappori, P.-A., and Weiss, Y. (2014). Economics of the Family. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bursztyn, L, Fujiwara, T., and Pallais, A. (2017). ‘Acting Wife’: Marriage Market Incentives and

Labor Market Investments.American Economic Review, 107(11), 3288-3319.

Buss, D. M. (1994). The Evolution of Desire. New York: Basic Books.

Buss, D. M. (2006). Strategies of Human Mating. Psychological Topics, 15(2), 239-260.

Choo, E., and Siow, A. (2006). Who marries whom and why. Journal of Political Economy, 114(1), 175-201.

Doleac, J. L., and Stein, L. C. (2013). The Visible Hand: Race and Online Market Outcomes.

Economic Journal, 123(572), 469–492. Online Dating Market代写

Eagly, A. H., and Wood, W. (1999). The origins of sex differences in human behavior: Evolved dispositions versus social roles. American psychologist, 54(6), 408-423.

Fernandez, R., Guner, N., and Knowles, J. (2005). Love and money: A theoretical and empirical analysis of household sorting and inequality. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(1), 273-344.

Finkel, E. J., Eastwick, P. W., and Matthews, J. (2007). Speed‐dating as an invaluable tool for studying romantic attraction: A methodological primer. Personal Relationships, 14(1), 149- 166.

Finkel, E. J., Eastwick, P. W., Karney, B. R., Reis, T. H., and Sprecher, S. (2012). Online dating: A critical analysis from the perspective of psychological science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(1), 3-66.

Fisman, R., Iyengar, S. S., Kamenica, E., and Simonson, I. (2006). Gender differences in mate selection: Evidence from a speed dating experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(2), 673-697.

Folke, O., andRickne, J. (2016).All the single ladies: Job promotions and the durability of marriage.IFN Working Paper no. 1146.

Fryer, R. G., and Levitt, S. D. (2004). The causes and consequences of distinctively black names.

Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(3), 767-805.

Gale, D., and Shapley, L. S. (1962). College admissions and the stability of marriage. American Mathematical Monthly, 69(1), 9-15.

Gautier, P. A., Svarer, M., and Teulings, C. N. (2010). Marriage and the city: Search frictions and sorting of singles. Journal of Urban Economics, 67(2), 206-218.

Glowsky, D. (2007). Why do German men marry women from less developed countries? An analysis of transnational partner search based on the German Socio-Economic Panel. Zeitschrift fur Soziologie, 36(3), 282-301.

Hitsch, G. J., Hortaçsu, A., and Ariely, D. (2010). Matching and sorting in online dating. American Economic Review, 100(1), 130–163.

Jalovaara, M., Neyer, G., Andersson, G., Dahlberg, J., Dommermuth, L., Fallesen, P., and Lappegård, T. (2017). Education, gender, and cohort fertility in the Nordic countries. Stockholm Research Reports in Demography(2017:6).

Kalmijn, M. (1998). Intermarriage and homogamy: Causes, patterns, trends. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 395-421.Online Dating Market代写

Klinenberg, E. (2012). Living alone is the new norm. Time Magazine, 179(10).

Kooiman, N., and Latten, J. (2014). More and more people access the internet to find partners. Statistics Netherlands (CBS online), June 19. https://www.cbs.nl/en- gb/news/2014/25/more-and-more-people-access-the-internet-to-find-partners.

Kurzban, R., and Weeden, J. (2005). HurryDate: Mate preferences in action. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26, 227–244.

Lundborg, P., Plug, E., and Würtz Rasmussen, A. (2017). Can women have children and a career?

IV evidence from IVF treatments. American Economic Review, 107(6), 1611-1637.

Regan, P. C. (1998). What if you can’t get what you want? Willingness to compromise ideal mate selection standards as a function of sex, mate value, and relationship context. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(12), 1294-1303.

Rosenfeld, M. J., and Thomas, R. J. (2012). Searching for a mate: The rise of the Internet as a social intermediary. American Sociological Review, 77(4), 523-547.

Schwartz, C. R., and Mare, R. D. (2005). Trends in educational assortative marriage from 1940 to 2003. Demography, 42(4), 621-646.

Skopek, J., Schulz, F., and Blossfeld, H-P. (2011). Who contacts whom? Educational homophily in online mate selection. European Sociological Review, 27(2), 180-195.

Smith, A., and Anderson, M. (2016). 5 facts about online dating. Retrieved May 5, 2017, from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/02/29/5-facts-about-online-dating/

Statistics Netherlands. (2014). Statistical yearbook of the Netherlands 2014. The Hague. Statistics Netherlands. (2017). Trends in the Netherlands 2017. The Hague.

Stewart, S., Stinnett, H., and Rosenfeld, L. B. (2000). Sex differences in desired characteristics of short-term and long-term relationship partners. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17(6), 843-853.Online Dating Market代写

Thottam, I. (2016). Retrieved May 5, 2017, from http://www.eharmony.com/online-dating- statistics/

Todd, P. M., Penke, L., Fasolo, B., and Lenton, A. P. (2007). Different cognitive processes underlie human mate choices and mate preferences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(38), 15011–15016.

Walster, E., Aronson, V., Abrahams, D., and Rottman, L. (1966). Importance of physical attractiveness in dating behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(5), 508-516.

Weiss, Y. (1997). The formation and dissolution of families: Why marry? Who marries whom?

And what happens upon divorce. Handbook of population and family economics, 81-123.

Wong, L. Y. (2003). Structural Estimation of Marriage Models. Journal of Labor Economics, 21(3), 699-727.

Tables

Table 3: Implementation of sending messages by round and gender

| Day | ||||||||||||||

| Treatment | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total | ||

| HS×LowAttr | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 120 | |||||||

| Uni×LowAttr | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 120 | |||||||

| HS×MedAttr | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 120 | |||||||

| Uni×MedAttr | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 120 | |||||||

| HS×HighAttr | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 120 | |||||||

| Uni×HighAttr | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 120 | |||||||

Notes: The six treatments are profile combinations of low attractiveness, medium attractiveness, high attractiveness, high school education, and university education.

Table 4: Descriptive statistics of website behavior

| Panel A: Men | N | Mean | S.D. | Min | Max | Median | |

| Opened message | 1554 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Replied to message | 1554 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Positive reply to message | 1554 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Days to reply | 492 | 6.8 | 21.5 | 0 | 194 | 0 | |

| Panel B: Women | |||||||

| Opened message | 1118 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Replied to message | 1118 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Positive reply to message | 1118 | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Days to reply | 180 | 9.3 | 24.7 | 0 | 221 | 1 |

Table 5: Effects of attractiveness and education on likelihood of response

| Female subjects | Male subjects | P-value | Female subjects | Male subjects | P-value | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| University | 0.001 | -0.051* | 0.098 | -0.002 | -0.026 | 0.518 |

| (0.019) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.033) | |||

| MediumAttr | 0.075*** | 0.131*** | 0.059 | 0.068** | 0.178*** | 0.014 |

| (0.020) | (0.025) | (0.026) | (0.037) | |||

| HighAttr | 0.203*** | 0.223*** | 0.417 | 0.205*** | 0.213*** | 0.783 |

| (0.025) | (0.027) | (0.035) | (0.038) | |||

| Uni×MediumAttr | 0.014 | -0.096 | 0.108 | |||

| (0.039) | (0.051) | |||||

| Uni×HighAttr | -0.004 | 0.022 | 0.649 | |||

| (0.047) | (0.054) | |||||

| Observations | 1117 | 1550 | 1117 | 1550 | ||

| Mean Response | 0.131 | 0.296 | 0.131 | 0.296 |

Notes:

The dependent variable is a dummy variable for any positive response from the online daters. All the responseregressions include constants and controls for the following characteristics of the online daters: age, time since last loginon dating site, province indicators, attractiveness indicators, day of the week indicators, dummy variable for demand for children, dummy variable for the fall wave, dummy variable for university degree. The independent profile variableseducation and attractiveness are dummy variables, with low attractive and without a university degree as the reference profile. The p-value is for the Ftest of equality across gender (low values indicate significant gender differences). Robust standard errors in parentheses.Online Dating Market代写

* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001

Table 6: Heterogeneous effects of attractiveness and education on likelihood of response

| All subjects | No Uni | Uni | P-value | Low Attr | Med Attr | High Attr | P-value | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Panel A: Response regressions on subsamples of female subjects | ||||||||

| University (0/1) | 0.001 | -0.019 | 0.125* | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.003 | -0.004 | 0.943 |

| (0.019) | (0.021) | (0.061) | (0.049) | (0.027) | (0.033) | |||

| MedAttr (0/1) | 0.075*** | 0.069*** | 0.092 | 0.403 | 0.064 | 0.089** | 0.046 | 0.537 |

| (0.020) | (0.021) | (0.066) | (0.053) | (0.027) | (0.028) | |||

| HighAttr (0/1) | 0.203*** | 0.202*** | 0.204** | 0.771 | 0.187*** | 0.227*** | 0.178*** | 0.718 |

| (0.025) | (0.027) | (0.068) | (0.062) | (0.035) | (0.042) | |||

| Observations | 1117 | 958 | 159 | 266 | 546 | 305 | ||

| Mean Response | 0.131 | 0.129 | 0.145 | 0.188 | 0.128 | 0.089 | ||

Panel B: Response regressions on subsamples of male subjects

| University (0/1) | -0.051* | -0.036 | -0.122* | 0.155 | -0.035 | -0.080* | -0.021 | 0.472 |

| (0.022) | (0.024) | (0.059) | (0.048) | (0.031) | (0.040) | |||

| MedAttr (0/1) | 0.131*** | 0.137*** | 0.111 | 0.944 | 0.200*** | 0.112** | 0.106* | 0.326 |

| (0.025) | (0.028) | (0.066) | (0.057) | (0.036) | (0.043) | |||

| HighAttr (0/1) | 0.223*** | 0.224*** | 0.184** | 0.890 | 0.223*** | 0.222*** | 0.210*** | 0.999 |

| (0.027) | (0.029) | (0.073) | (0.061) | (0.038) | (0.048) | |||

| Observations | 1550 | 1325 | 225 | 380 | 773 | 397 | ||

| Mean Response | 0.296 | 0.299 | 0.279 | 0.374 | 0.307 | 0.202 |

Notes:

The dependent variable is a dummy variable for any positive response from the online daters. The independent profile variables education and attractiveness are dummy variables, with low attractive and without a university degree asthe reference profile. All response regressions include the following characteristics of the online daters: age, province indicators, dummy variable for demand for children, time since last login on dating site; dummy variable for the fall wave;day of the week indicators;Online Dating Market代写

education measured in dummies in columns (5) to (7); attractiveness measured in dummies in columns (2) and (3). Column (1) contains estimates of response regressions run on full samples. Columns (2) to (3) contain estimates of response regressions run on education subsamples. Columns (5) to (7) contain estimates of response regressions run on attractiveness subsamples. The p-value is for the F-test of equality across the different education andattractiveness samples (low values indicate significant sample differences). Robust standard errors in parentheses. * p<0.05,** p<0.01, *** p<0.001

Figures

Appendix

A.2 Tables Online Dating Market代写

Table A2: Share preferring one of our two profile photos in pair-wise comparisons

| Attractiveness | Female Pairs | Male Pairs |

| Low | 0.495 (0.784) | 0.555 (0.010) |

| Medium | 0.480 (0.244) | 0.454 (0.033) |

| High | 0.523 (0.100) | 0.518 (0.410) |

| N | 850 | 531 |

Notes: p-values from t-tests of whether the mean is equal to 0.5 in parentheses.

A.3 Messages Online Dating Market代写

Invitation message (translated from Dutch):

Hi! I just saw your profile and you seem really nice and interesting. My name is [username] and I’m looking for a long-term relationship. I would really want to get to know you, and see what it leads to. If you find me interesting as well perhaps we could find some time to chat or even meet?

Best, [username]

Reply message (translated from Dutch):

First of all, thanks for your kind response and shown interest in me! However, I have to let you know there is another person I have been dating and I now want to devote all my attention to him/her. Therefore, I decided not to meet with anyone else right now.

All the best, [username]

其他更多:C++代写 r代写 代码代写 金融代写 物理代写 考试助攻 C语言代写 finance代写 lab代写 计算机代写 code代写 data代写 report代写 代写CS matlab代写 统计代写